Systemic Racism is Alive and Well in Healthcare

How Implicit Bias among Clinicians has Effectively Made Schizophrenia a “Black Disease”

Image by Tim Mossholder via unsplash

As this country has come to renewed grips with its racist past and present in recent years, it is painfully apparent that institutionalized discrimination still pervades almost every institution in America. Healthcare should be an objective and unbiased way to identify illness and ailment in patients and help them live better lives; however, it is not exempt from institutionalized racism. In this blog post, I will discuss how clinicians are more likely to diagnose Black Americans with schizophrenia than White Americans with the same symptoms.

Multiple studies and reports have revealed that Black Americans are up to five times as likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia as non-Hispanic White patients. Studies such as the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study have confirmed that there is also no genetic or epidemiological basis behind why rates of schizophrenia would be higher in Black Americans than Whites. There is thus no reason that Black patients receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia on more occasions than White patients other than implicit bias on the part of the clinician. A fivefold increase in diagnosis of a disorder as serious as schizophrenia is nothing to scoff at — how did we get here?

Research into this topic

Research has started to gain steam in the late 80’s, and a number of pioneering studies — such as Barnes and colleagues’ 2004 analysis of patient health data across state psychiatric hospitals in Indiana throughout the late 80’s and early 90’s — started to bring this issue to mainstream attention. Even as the Black American population of Indiana slowly increased (from around 7% in the late 80’s), this group was still grossly overrepresented in diagnoses of schizophrenia in the state’s psychiatric hospitals. In 1994, Black patients accounted for 36% of these diagnoses while only making up around 8% of the state’s total population.

A similar study in Tennessee in 1994 found that 48% of patients in the state’s psychiatric hospitals who had received a diagnosis of schizophrenia were Black, a group that only made up 16% of the state’s population at that time. It was clear there was an issue here that warranted further investigation — an issue that still affects thousands of Black Americans each year.

These findings still hold true when controlling for other influencing factors such as gender, age, education, or income, as shown by Gara and colleagues in a breakthrough 2012 study. Gara’s team gathered medical records and transcribed interview data from patients with various psychiatric disorders from among six major medical institutions from across the country, including UCLA and the University of Michigan. A team of editors redacted any identifying features conveyed through the patient records, including ethnic cues from the transcribed interviews. They then gathered clinical experts — mostly psychiatrists — and asked them to make diagnoses based on the patient data. The researchers found that even after controlling for all these factors, there was still a significant correlation between the self-reported ethnic identification of the patient on the medical record and a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Researchers also found similar results when comparing the schizophrenia diagnosis rates of Hispanic patients to Whites. It is clear that the implicit bias of clinicians — among which minority practitioners are historically underrepresented — was adversely affecting diagnostic outcomes for minority patients, an issue that still pervades doctor’s offices and psychiatric hospitals today.

This overrepresentation of schizophrenia diagnosis isn’t just a statistical anomaly

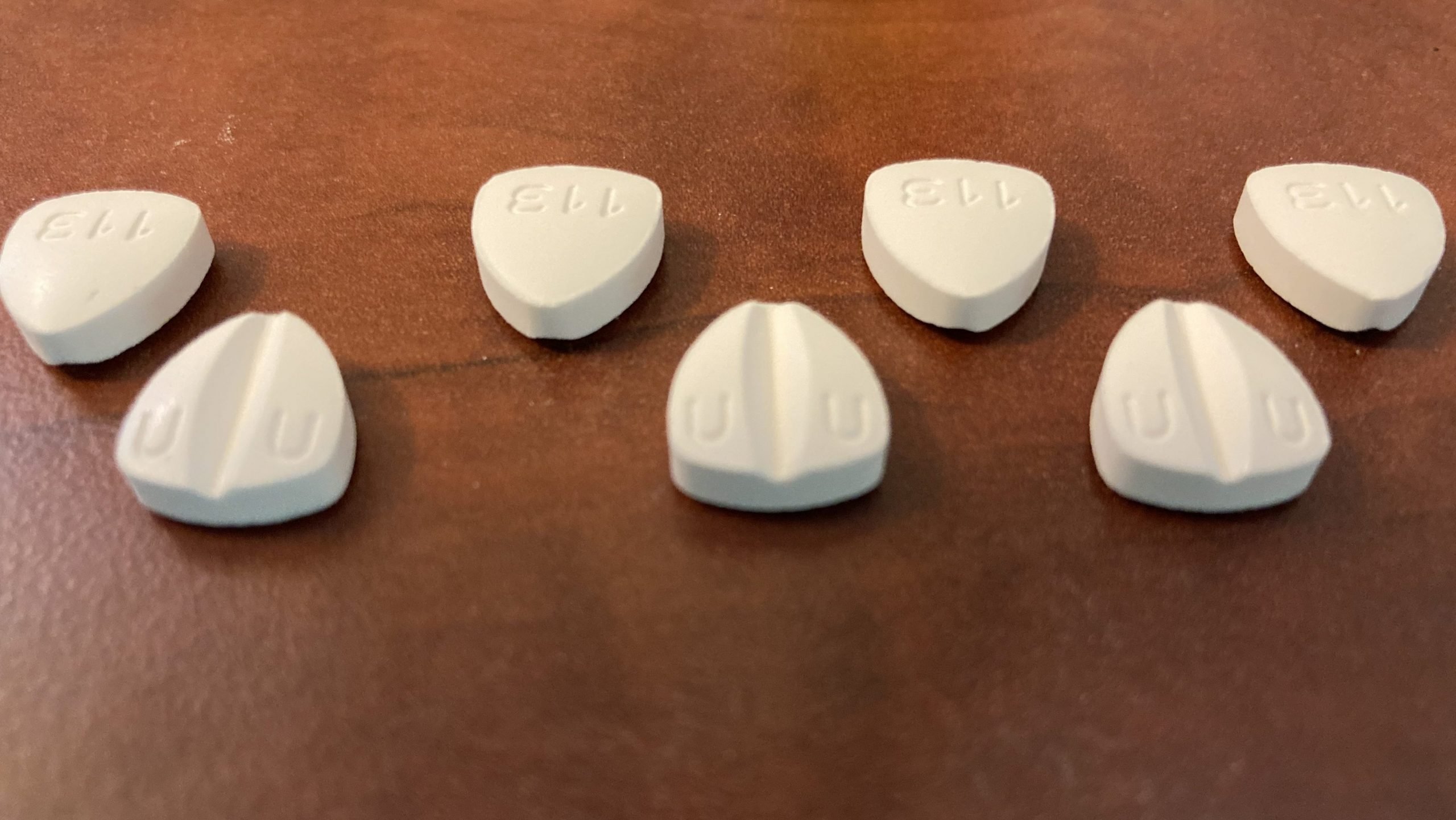

— it has profound and real effects on the lives of those who are misdiagnosed. An incorrect diagnosis of schizophrenia can lead to a patient with a mood disorder being prescribed antipsychotic medications. This can lead to further adverse effects on the patient if they do not actually have the disorder that the drug is supposed to target. A misdiagnosis of schizophrenia can also lead to additional discrimination or social stigmatization against the diagnosed patient, and increase their risk of subsequent hospitalizations or suicide.

This disproportionate increase in schizophrenia diagnoses is also often coupled with an underrepresentation of diagnoses of mood disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder.

Essentially, it would seem as if clinicians are more likely to interpret Black American patients as presenting with psychotic symptoms as opposed to their White counterparts, when both are equally as likely to have a mood disorder or schizophrenia.

Gara and colleagues have suggested three main factors that might contribute to this kind of inequality in diagnosis:

Possible Reasons for these Disparities:

- Diagnostic basis of clinicians

- The DSM, used in the U.S. to diagnose psychiatric disorders, has gone through numerous changes, including many that have tried to account for cultural differences in patients when giving a diagnosis

- The real-world effects of these changes to the text of the DSM are questionable.

- Barnes and colleagues actually observed an increase in schizophrenia diagnoses among Black Americans in Indiana from when the DSM IV — which incorporated “cultural features” into its diagnostic criteria for the first time — started to be used in 1994

- Racial differences in presentation of psychiatric symptoms

- Black Americans with mood disorders may be more likely to be interpreted as presenting with psychosis due to:

- Cultural differences in worldview based on previous discriminatory experiences; i.e. “healthy paranoia”

- Culturally or historically influenced mistrust of clinicians or the healthcare institutions in general

- Cultural differences in presenting mental illness based on differing cultural norms, customs, or practices

- Delayed seeking of treatment (due to disproportionate allocation of available psychiatric healthcare resources) leading to more severe symptoms when finally diagnosed

- Black Americans with mood disorders may be more likely to be interpreted as presenting with psychosis due to:

- A Strained Patient-Clinician Relationship

- Eack and colleagues state how the most influential predictor of a clinician giving a schizophrenia diagnosis to an Black American patient was how “honest” and “trustworthy” they perceive the patient to be

- This speaks to a cultural disconnect between patients and doctors that is fueling this diagnostic divide

- There is a serious shortage of Black and Hispanic doctors in the United States that does not reflect its ethnic makeup

- Minority patients feel more comfortable, trustful, and at ease when interacting with healthcare providers from their same ethnic group

- The distrust minority patients may feel towards their clinician may be affecting their presented symptomatology and diagnosis.

- We need to expand educational opportunities so that minority patients who are underrepresented in medicine can more easily access a medical education

- Influenced by a far-reaching history of segregation, redlining, and gerrymandering in minority-predominant neighborhoods

- These need to be addressed (i.e. through redistricting, affordable housing developments, outreach programs to minority-predominant neighborhoods) if we want to see lasting changes in the racial makeup of clinicians

- The current system of medical education in America caters itself to affluent White applicants and those with family members already in medicine

- Eack and colleagues state how the most influential predictor of a clinician giving a schizophrenia diagnosis to an Black American patient was how “honest” and “trustworthy” they perceive the patient to be

Image by Alex Green via unsplash

Conclusion

Flawed diagnostic tools, racial differences in symptom presentation, and a cultural disconnect between clinicians and minority patients represent just a few of the possible factors that may be influencing these differences in schizophrenia diagnosis. While more research is needed to identify what more specific factors in symptom presentation could be influencing these diagnostic outcomes, it is clear that the current system in America is failing Black American patients due to diagnoses influenced by clinicians’ implicit biases.

In a country that is only becoming more and more diverse, it is imperative that we reconsider the way we approach situations in which there might be cultural barriers that affect the perception of symptoms of mental illness. Our diagnostic criteria for mental illness need to be changed to truly be more culturally aware and cognizant of these cultural differences so that clinicians can better serve minority patients. It is also crucial that we address educational disparities in minority-predominant communities so that more students from these underserved groups are able to access a medical education and better serve patients who may be from these same communities. Such advances are going to take time and require fundamental change on a broader societal level to address racial discrimination and inequality within minority communities who have been mistreated and left voiceless for far too long in this country.

References

Schwartz, R. C., & Blankenship, D. M. (2014). Racial disparities in psychotic disorder diagnosis: A review of empirical literature. World journal of psychiatry, 4(4), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i4.133

Eack, S. M., Bahorik, A. L., Newhill, C. E., Neighbors, H. W., & Davis, L. E. (2012). Interviewer-perceived honesty as a mediator of racial disparities in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.), 63(9), 875–880. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100388

Barnes A. Race, schizophrenia, and admission to state psychiatric hospitals. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2004 Jan;31(3):241-52. doi: 10.1023/b:apih.0000018832.73673.54. PMID: 15160786.

Barnes A. Race and hospital diagnoses of schizophrenia and mood disorders. Soc Work. 2008 Jan;53(1):77-83. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.1.77. PMID: 18610823.

Gara MA, Vega WA, Arndt S, Escamilla M, Fleck DE, Lawson WB, Lesser I, Neighbors HW, Wilson DR, Arnold LM, Strakowski SM. Influence of patient race and ethnicity on clinical assessment in patients with affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Jun;69(6):593-600. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2040. PMID: 22309972.